Why a common currency

An economic and monetary union (EMU) was a recurring ambition for the European Union from the late 1960s onwards. Creating an EMU involves coordinating economic and fiscal policies, a common monetary policy, and a common currency, the euro. A single currency offers many advantages by

- making it easier for companies to trade across borders

- allowing people to travel, live, work and study abroad more easily

- keeping prices stable.

However, several political and economic obstacles barred the way: weak political commitment, divisions over economic priorities, and turbulence in international markets. These all played their role in slowing progress towards Economic and Monetary Union.

The path to the euro

The international currency stability that reigned in the immediate post-war period did not last. Turmoil in international currency markets threatened the common price system of the common agricultural policy, a main pillar of what was then the European Economic Community. Later attempts to achieve stable exchange rates were hit by oil crises and other shocks until, in 1979, the European Monetary System (EMS) was launched.

The EMS was built on a system of exchange rates used to keep participating currencies within a narrow band. This completely new approach represented an unprecedented coordination of monetary policies between EU countries, and operated successfully for over a decade.

From Maastricht to the euro and the euro area

Under Jacques Delors, the then President of the European Commission, central bank governors of the EU countries produced the 'Delors Report' in 1989 on how the Economic and Monetary Union could be achieved. They proposed a three-stage preparatory period, spanning the period 1990 to 1999. European leaders accepted these recommendations.

In December 1991, the European Council agreed the new Treaty on European Union, also known as the Maastricht Treaty, which contained the provisions needed to implement the monetary union.

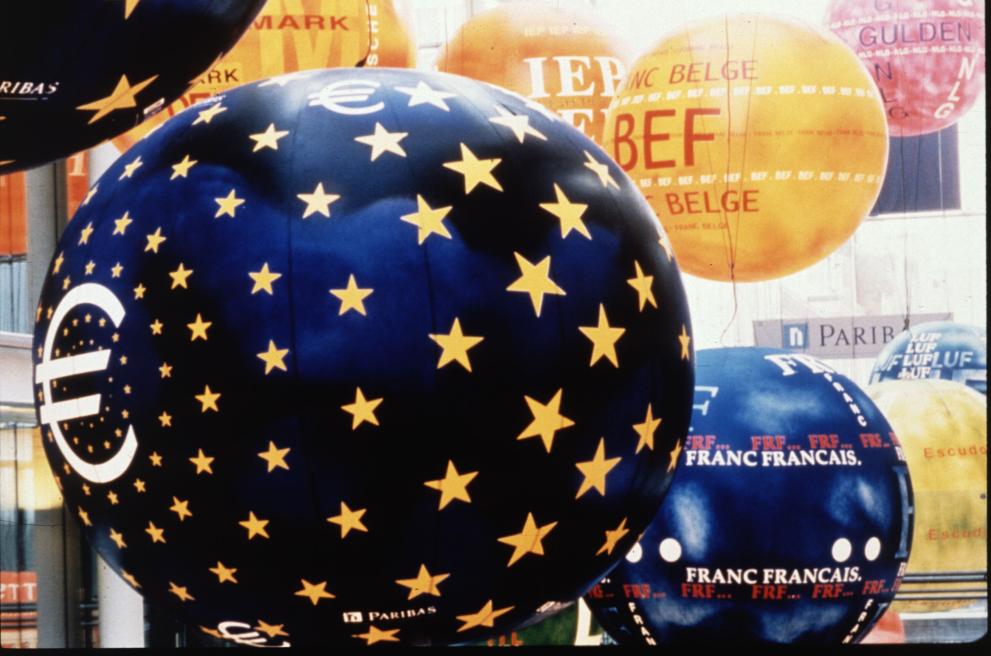

After a decade of preparations, the euro was launched on 1 January 1999. For the first three years it was an ‘invisible’ currency, only used for accounting purposes and electronic payments. Coins and banknotes were launched on 1 January 2002 in 12 EU countries which was the biggest cash changeover in history.

More than 350 million Europeans in 21 EU countries now use the single currency every day, which makes it a tangible symbol of European integration. More countries are preparing to adopt it in the future.